Analysis

Renata Venero

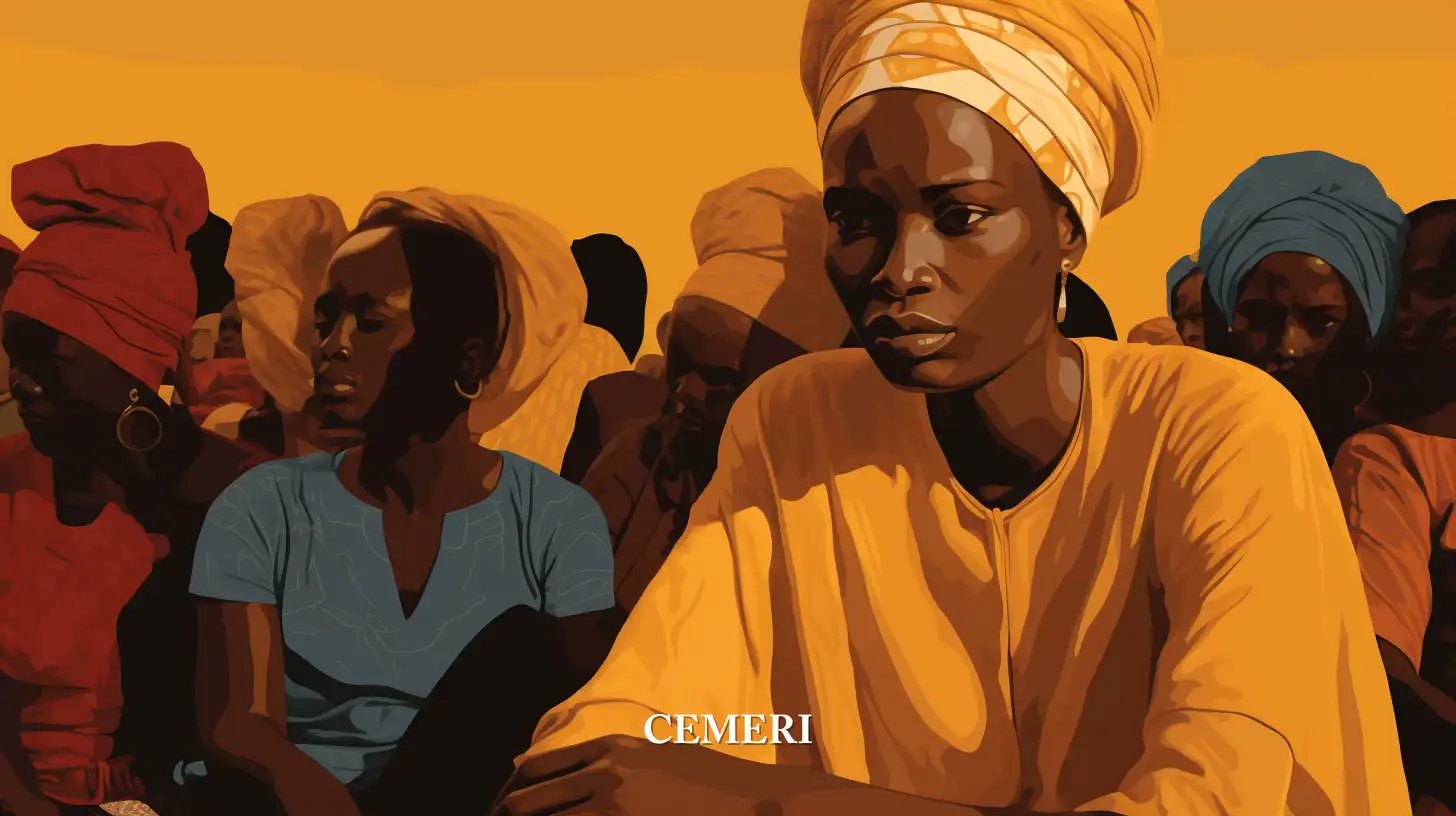

Democratic Republic of the Congo: sexual violence as a perpetual weapon

- The Democratic Republic of the Congo was considered by the UN Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict, Margot Wallström, as the rape capital of the world in 2010.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was considered in 2010, by the UN Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict, Margot Wallström, as the world capital of rape, since this has been used in its armed conflicts as a weapon of war and control (Nanivazo, 2015).

It is a place that, since its colonial independence, has been marked by constant humanitarian crises, displacements, and internal conflicts, which considerably increase the chances that the most vulnerable people may suffer abuses of their human rights, their physical condition, and their health. human integrity.

Despite the peace agreement in 2002, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo these acts of violence continue to be perpetuated where women, girls and boys are the most affected. To date, the territorial crisis in the DRC has made life for these people more precarious. For this reason, this text will address this problem that affects and terrifies the entire population of the DRC.

Mainly, with the intention of knowing in depth the situations that gave rise to the rape of many people perpetuated in the territory, it is necessary to carry out a brief historical account of the delimitations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in order to understand the context in which they were carried out. developed this problem.

In 1960, the territory of the current Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Belgian Congo achieved independence, later to become Zaire under the dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko. During Mobutu's government, the country was subjected to an authoritarian, violent and kleptocratic government, which ruined the political, economic, social and territorial stability of the country, mainly affecting the population (Scaramutti, 2014, p.3).

Later, the fall of Mobutu Sese Seko caused, in 1996, the start of a civil war, known as the First Congo War, which lasted two years. This confrontation became a continental conflict, known as the Second Congo War or the Great African War (Royo Aspa, 2016).

This dispute is considered continental in nature since more than seven African countries were involved, such as Angola, Chad, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Libya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as armed groups and militias with their own interests. (Scaramutti, 2014, p.3).

Additionally, the Great African War has been considered one of the worst misfortunes that has happened on the continent, leaving a balance of nearly five million dead, 3.4 million refugees, as well as an uncountable number of war crimes and massive rapes (UNHCR, 2021).

After four years of disputes, in 2002, United Nations peacekeepers intervened in the conflict with the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the signing of the Pretoria Global and Inclusive Agreement was achieved, which it ended the conflict and the beginning of the establishment of a democratic system in the DRC (Royo Aspa, 2016).

In the period of the Second Congo War, mentioned above, violence, mainly sexual violence, was used as a weapon of mass war, to sow fear and control in the communities where the militias and armed groups passed through.

In addition to the above, it is known that sexual violence is

One of the most used weapons of war in armed conflicts, not only as a means of subjugation, but also as an instrument of collective terror that causes a high number of situations of armed and political violence to be present after the period of wars ( Scaramutti, 2014, p.5).

In addition, this tactic is also used as a way of humiliating and degrading the enemy. Therefore, it shows that the victims of these massive violations could have been women, girls, boys and men, since their purpose is to systematize fear in their enemies, be it the latter, the civil population, different ethnic groups or members of the opposing guerrillas.

It should be noted that sexual violence as a weapon in wartime is not a new phenomenon, it is as old as war itself. Mass rape has been used in multiple armed conflicts, such as in Rwanda (1994), Kosovo (1998-1999), Sierra Leone (1991-2002), Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1995), to name a few. However, the case of the DRC had a greater international impact due to the magnitude and nature of the crimes committed (Nanivazo, 2015).

Mathilde Muhindo was one of the first activists to give voice to the crimes that occurred in the second war in the DRC, as well as to take courage to denounce the abuses committed against the civilian population. Mathilde Muhindo spoke about how Rwandan and Burundian combatants, involved in the Great African War, were using rape as a weapon of war (Deiros Bronte, 2020, p.6).

Muhindo described the phenomenon as:

It was from 1998. Our agents from the Olame center of the Congolese Catholic Church who were traveling through South Kivu began to come across villages from which the entire population had fled. Upon arrival, little by little, women and girls began to emerge from the forests. Virtually all had been raped. This could not be a coincidence: these attacks were used to physically and psychologically destroy women and, through them, families and communities.

Muhindo in Deiros Bronte, 2020, p. 6

For a long time these atrocities became more frequent and intense, however, the International Community was unaware of the existence of crimes against the population. It was not until 2002, with the entry of peacekeeping missions by the United Nations and humanitarian aid from international organizations, that mass rapes became known internationally (Deiros Bronte, 2020, p.6).

In the same way, in the same year, Human Rights Watch (HRW) made visible the great problem through its report A war within a war, in which the reality was described. To mention some of the things that are raised in your report. HRW refers to the cases of soldiers and combatants who raped and abused, mainly, women and girls as part of their effort to maintain control over civilians and territories (Human Rights Watch, 2002, p.23).

In October 2004, Amnesty International estimated that there have been close to 40,000 cases of rape in the last six years, since 1998, most of them in South Kivu (Amnesty International, 2004). Despite being aware of the brutal crimes committed in the DRC, there is no full estimate of what happened, because many of the cases were not reported by the victims out of fear. Which means that the figures obtained in the years after the conflict can be doubled or even tripled.

Unfortunately, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, during and after hostilities, victims of sexual violence, after having been the victim of these inhumane acts, are revictimized and condemned by society. Often, they not only suffer physical and psychological consequences, but also pay a high price for not being condemned by their communities (ICRC, 2018).

In particular, the victims suffer the rejection of their own families and members of their community, they are removed from participating in social activities and even expelled from their homes. For this reason, victims of rape are afraid to talk about their cases, ask for help and denounce their aggressor (Scaramutti, 2014, p.4).

Currently, despite all the attempts to improve conditions in the DRC and seek stability in the territory, the tense relations of the armed groups, as well as impunity and a weak rule of law, have caused the situation of conflict and violence remain in the territory and serious violence against human rights continues to occur.

In the post-war period, the number of victims of rape continued to rise sharply. In 2014, Doctors Without Borders reported that cases of sexual violence have remained widespread in the country, having a constant and significant increase (Doctors Without Borders, 2021, p.11).

From then until 2020, the United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) documented 1,053 cases of conflict-related sexual violence, affecting 675 women, 370 girls, 3 men and 5 boys (United Nations United, 2021).

On the other hand, it was pointed out that sexual violence in the DRC is not only linked to the armed conflict, but also that, every day, women, girls, men and boys are sexually assaulted by people who do not directly participate in the hostilities, even in secondary conflict zones, and this remains an important and often overlooked component of the problem of sexual violence (United Nations, 2021).

Finally, the foregoing shows that rape as a weapon of war continues to be used to date and that said weapon is being used by those civilians who are not involved in the conflict. In the same way, this happens because there is zero action by the authorities to prevent more cases of rape, in addition to a high level of impunity and injustice in the reported cases.

Sources

ACNUR. (13 de agosto de 2021). República Democrática del Congo: ACNUR gravemente preocupado por la violencia sexual sistemática en la provincia de Tanganica. ACNUR España Sitio Web. https://www.acnur.org/noticias/briefing/2021/8/611689854/republica-democratica-del-congo-acnur-gravemente-preocupado-por-la-violencia.html

Amnistía Internacional. (2004). República Democrática del Congo violación masiva: Tiempo de soluciones. Amnistía Internacional. 67. https://www.cear.es/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/R-D.-CONGO.-2013.-Situacion-de-ninos-y-ninas.pdf

CICR. (07 de agosto de 2018). Las mujeres en la Republica Democrática del Congo (RDC). Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja sitio web. https://www.icrc.org/es/where-we-work/africa/republica-democratica-del-congo/mujeres

Deiros Bronte, Trinidad. (20 de enero de 2020). Violencia sexual en Congo: el estereotipo del «arma de guerra» y sus peligrosas consecuencias. 24. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_marco/2020/DIEEEM01_2020TRIDEI_Congo.pdf

Human Rights Watch. (junio 2002). La guerra dentro de la guerra: Violencia sexual contra mujeres y niñas en el este del Congo. 128. https://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/drc/Congo0602.pdf

Médicos Sin Fronteras. (15 de julio de 2021). Informe Violencia sexual en la República Democrática del Congo. 22. https://www.msf.org/sexual-violence-democratic-republic-congo

Médicos Sin Fronteras. (15 de julio de 2021). República Democrática del Congo: pedimos que la violencia sexual sea considerada una emergencia. Médicos Sin Fronteras Sitio web. https://www.msf.es/actualidad/republica-democratica-del-congo/republica-democratica-del-congo-pedimos-que-la-violencia

Naciones Unidas. (30 de marzo de 2021). Informe del Secretario General al Consejo de Seguridad (S/2021/312). https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20the%20United%20Nations,dated%20back%20to%20previous%20years

Nanivazo, Malokele. (2015). Violencia sexual en la República Democrática del Congo. United Nations University. https://unu.edu/publications/articles/sexual-violence-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo.html

Royo Aspa, Josep María. (13 noviembre de 2016). Los Orígenes del Conflicto en República Democrática del Congo. Africaye.org. https://www.africaye.org/origenes-conflicto-republica-democratica-congo/

Scaramutti, Mayra. (2014). República Democrática del Congo: Violencia sexual masculina como arma de guerra. Departamento África del IRI-UNLP. https://www.iri.edu.ar/images/Documentos/trabajo_alumnos/scaramutti_2014.pdf