Encyclopedia

CEMERI

Who owns the Arctic?

- The dispute over Arctic sovereignty may seem absurd, given the icy and inhospitable nature of that place; however, several countries have it in their sights.

The Arctic, like many other ecosystems on planet earth, is undergoing severe modifications caused by climate change. Dhaka University Model United Nations Association, DUMUNA, assures that this great frozen block, located at the North Pole of the globe, is gradually melting thanks to the increase in temperatures and, with it, more countries join the fight to obtain control over him (2020, par. 1).

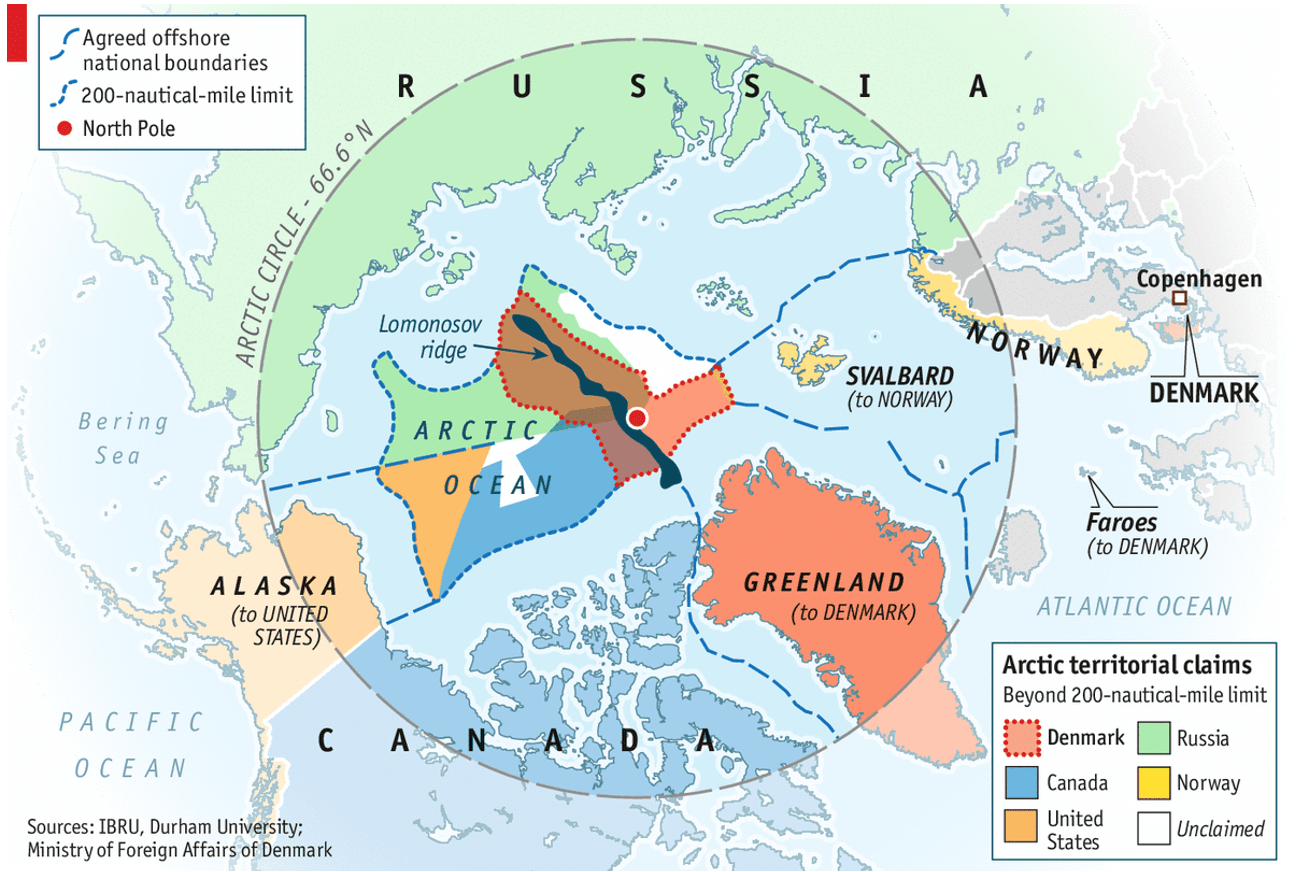

At first, this "dispute" over the sovereignty of the Arctic may seem absurd, given the icy and inhospitable nature of that place, however, a deeper analysis is necessary. According to the United States Geological Survey, below the Arctic lie approximately 22% of the world's oil and gas reserves; In addition, the maritime route that emerged from the thaw has the potential to replace the Suez Canal (DUMUNA, 2020, par. 1).

When these two characteristics with high geopolitical and geostrategic value are combined, see energy reserves and new commercial maritime routes, the Arctic conflict makes sense. The good news is that the debate about who can control and exploit that frozen territory has taken place in the United Nations, UN, and the dispute settlement mechanisms of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS (Carlson, Hubach , Long, Minteer & Young, 2013, p. 28). However, the risk of a war conflict as a result of the Arctic cannot be ruled out 100%, especially with the growing militarization in its vicinity.

Contemporary historical context: from the cold war to UNCLOS

From 1940 onwards, the Arctic became a strategic zone because the world discovered that this region represented the shortest distance between America, Europe and Asia, either for better or for worse (Piffero, da Silva, Gimenez, Lersch & Gihad, 2013, p.15). During World War II, this proximity was used by the allies to coordinate collaborative military strategies against the axis; however, the situation changed radically by 1950, the year in which the Arctic became a region of tension and military escalation (Piffero et al. al., 2013, pp. 15-16).

Another situation that functioned as a catalyst for the conflict was the United States under the Truman presidency. The former US president proclaimed a policy that allowed his country to unilaterally extract marine natural resources, which the UN fought with the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf, a legal document approved by all countries except Iceland (DUMUNA, 2020). , par. 6). If the possible legal disputes were contained for a few years with the UN action, the military escalation did not stop at all.

Between the early 1950s and the late 1970s, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom built several anti-missile systems in Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland, while the Soviet Union did the same, placing nuclear submarines in the surrounding area (Piffero et al. al., 2013, pp. 16-17). During those years, diplomatic confrontations over the Arctic resurfaced. In 1972, the Kingdom of Denmark and Canada sent the UN their "legal agreement" on the Arctic territories, a movement that generated unrest and discord in other countries such as the Soviet Union (DUMUNA, 2020, par. 7).

It wasn't until the 1980s that the escalating military and diplomatic issues underwent major changes. On October 1, 1987, Gorbachev, former leader of the Soviet Union, declared the "Murmansk Initiative" where he called for the cessation of hostile nature at the North Pole and scientific collaboration in that region with the United States and the rest of the world ( Piffero et al., 2013, p.17). On the diplomatic side, the claims acquired an institutionalized nature with article 76 of UNCLOS, which allows a member state, if it provides geological evidence that a distant seabed belongs to its continental shelf, to acquire control over that territory (DUMUNA, 2020, pars 8-10).

In other words, UNCLOS allows its participants to claim marine areas that are beyond their exclusive economic zone, EEZ, if they prove with scientific evidence that those regions are located on their continental shelf. Thanks to the above, countries like Canada, Russia, Denmark and Norway have used that same UNCLOS article to seek to impose their sovereignty over the Arctic in recent times.

Russian claims

In December 2001, the Russian Federation, after signing and ratifying UNCLOS in 1997, became the first country to request an extension of its EEZ towards the Arctic, however, its request was rejected at the UN (Carlson et al., 2013, p.28). Despite the refusal, Russia did not give up and, over the next few years, continued to undertake new actions with the aim of taking control of the Arctic. The Kremlin's next move on the issue occurred in 2007, the year in which the Russian explorers visited the region to collect information on the oil located there, plant a flag of the Russian Federation and declare the “return” of their country as a greater power (Carlson et al., 2013, p. 29).

Fourteen years after those events, Russia sent a new request to the UN, again based on article 76 of UNCLOS, with scientific evidence to be able to extend its EEZ towards the Arctic to such a degree that it invades the area of Canada, seeking a approximate expansion of 705,000 square kilometers (Tranter, 2021, par. 5). Since the request was sent in 2021, there is still no response from the UN and uncertainty remains. Until now, all of Russia's previous actions have been in the diplomatic sphere, however, the other strategy used by the Kremlin to seize control over the North Pole remains to be analyzed: a military escalation.

Contrary to the wishes of his predecessor, Vladimir Putin has sought to restore the Russian military presence in the Arctic bit by bit; In 2008, directed military spending for operations in that area was 58 billion dollars, seven years later the figure increased to 90 billion dollars (Petersen & Pincus, 2021, p. 492). Also, the current Russian government has directed large economic resources to modernize the entire technological system present at the North Pole. In 2018, Nikolai Yeymenov, Russia's military commander for the Arctic, explained that the modernization of the radio, wiring, communications, infrastructure and anti-missile defense system seeks to create an anti-missile "shield" for Russia, a goal that was impossible with previous Soviet equipment. to renewal (Petersen & Pincus, 2021, p. 493).

Everything seems to indicate that the Russian military escalation in the Arctic is not going to stop in the near future for two reasons: defense and energy potential. According to several Russian strategists, control over the North Pole is a danger to their national security because certain States and military coalitions, such as the Atlantic Alliance, NATO, seek to dominate that region with the intention of intimidating Russia (Petersen & Pincus, 2021). , p.497). Regarding the energy side, if Putin succeeds in taking over most of the Arctic, he would consolidate Russia as the undisputed energy leader, giving it the power to dominate the world oil and gas markets (Carlson et al., 2013, p. 30). .

Canadian Claims

Although Canada has been making claims to the arctic since the beginning of the 20th century, it was not until 1969 that it made an official and serious statement when an American company tried to enter the frozen area belonging to the Canadian government (Carlson et al., 2013, p. 31). . As a consequence, Ottawa has had quite a few run-ins with governments near the North Pole. The closest is with the United States and it is about a specific dispute over the Beaufort Sea, while Denmark, via Greenland, the conflict lands on the Hans Islands, tracts of land very close to the Arctic (Carlson et al., 2013, p. 32).

Unlike Russia, Canada has not undertaken such large military actions in the vicinity of that territory. The only operation or militarization undertaken by the Canadian government occurred in 2005, the year in which the Ottawa army went to the Hans Islands to remove the Danish flag to replace it with a Canadian one (Carlson et al., 2013, p. 32). . Time passed and Canada, after gathering a lot of scientific evidence, made its next move years later. Now becoming the third country to claim that it should have sovereignty over much of the Arctic based on article 76 of UNCLOS, Canada sent its request to the UN in 2019 (Kemeny, 2019, par. 1). There is still no response from the UN to Canada's request, which probably won't change for quite some time considering Russia's and Denmark's claim.

Danish claims

The case of Denmark cannot be understood if it is not emphasized that this country has control over Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Given its proximity to the Arctic, the two aforementioned territories make it much easier for the Danish government on the matter, however, its actions had to wait until 2014 because it was not until 2004 when it ratified UNCLOS (Carlson et al., 2013, p. 33). Thus, and based on article 76 of the convention, in 2014 Denmark, together with Greenland and the Faroe Islands, sent its request to the UN to have control over 350,000 square miles in the Arctic (Calamur, 2014, par. 1 ). Like Canada, Denmark has not taken large-scale military action because of the North Pole, but that does not translate into ignorance or arrogance in the Danish government. Right after sending the request to the UN, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Denmark stated that his country's positioning could lead to diplomatic conflicts with Norway, Canada, Russia and the United States (Calamur, 2014). Like the Russian and Canadian requests, Denmark has not received a response from the UN either.

What about the US and China?

Both countries, unlike Russia, Canada and Denmark, have not made Arctic claims based on UNCLOS Article 76. In the case of the United States, as it is not a member of the convention, it is impossible for it to make a claim like this, so it has used other mechanisms, see the statement in 2008 where, supposedly, the Alaskan EEZ reached the Arctic ( Carlson et al., 2013, p.37). Since then, the United States has maintained a vigilant stance over control of the North Pole and its energy resources. In 2013, the Secretary of Defense of the United States affirmed that the Arctic has become a matter of great importance for his country, which is willing to collaborate with its allies to achieve its strategic objectives in the area (Lundestad & Tunsjø, 2015, p.392).

In the case of China, the situation is more complex in the Arctic. Even though Beijing is part of UNCLOS, that legal document does not allow it to make a claim like those made by Canada because China is not geographically close to the North Pole. Thanks to that, the Chinese government's stance has been more discreet and closed. For example, its most concrete action has been its admission as an observer country to the Arctic Council in 2013; China does not have an "official" policy towards the Arctic like the other countries interested in the matter (Lundestad & Tunsjø, 2015, p. 395). So, the Chinese position can be interpreted as a "wait and see" towards recent events in the Arctic since, for the Chinese government, since the 1990s this inhospitable region of the earth has been very attractive for scientific research (Lundestad & Tunsjø, 2015, p.395).

Reclamaciones territoriales del Ártico. Disponible en: https://geografia.laguia2000.com/hidrografia/reclamaciones-territoriales-en-el-artico

Sources

Fischetti, Mark. (2019). ''A quién pertenece el Ártico?. Investigación y Ciencia, no. 517, pp. 22-30. Recuperado de: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7156895